Letter from South Africa: A Long Walk through the Apartheid Museum

In the heavily computerized age we live in, a myriad of information is always accessible at the click of a fingertip.

In the heavily computerized age we live in, a myriad of information is always accessible at the click of a fingertip.

It has become easier for one to know more about all the injustices that have taken place throughout history and continue to happen everywhere.

However, it remains quite a challenge to fully understand and grasp the extent to which everything happened or the effects and implications they may have had because of how everything has become watered down into numbers in history books.

Take the word ‘apartheid’ for example — rarely does the mere mention of the word ever convey many feelings or emotions upon hearing it, regardless of all the cruelty it is charged with.

I, for one, often prided myself in knowing what I thought to be enough about apartheid South Africa.

I always believed I knew a lot about the levels of cruelty and injustices that prevailed, which is nothing short from the truth. No amount of African history classes, readings, pictures, or even videos could have prepared me enough for what I saw at Johannesburg’s Apartheid Museum.

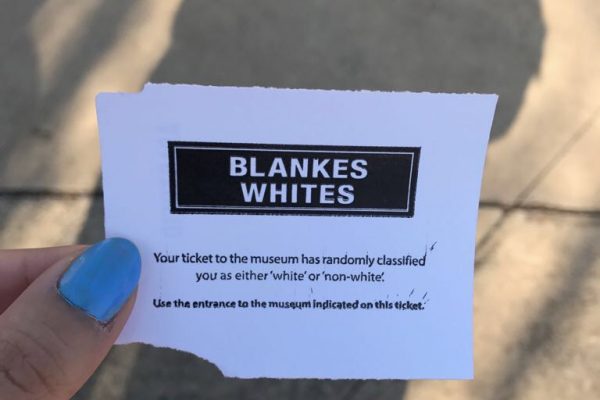

Upon stepping foot into the museum, I was handed a slip of paper that read “BLANKES WHITES — your ticket to the museum, has randomly classified you as either ‘white’ or ‘non-white.’ Use the entrance to the museum indicated on this ticket.”

Baffled at the piece of paper in my hand, I spent some time trying to make sense of what that meant exactly.

I was more shocked upon looking up at the gate of the museum to find two doors, labeled in Afrikaans: Blankes (whites) and Nie-Blankes (non-whites).

A feeling of confusion, shock, and disgust swept through me and I found my feet glued to the ground and my mind racing, trying to make sense of what stands before me.

The tour guide’s voice interrupted my thoughts, bringing me back to the moment, as he explained how the museum is designed in a manner that gives visitors the chance to see first-hand how the system of apartheid was executed.

At the very first step into the museum, I was bombarded with a sea of ID cards and pass books hanging from the ceiling.

A number of signs adorned the walls, each indicating which color gets to use a staircase or wait at the taxi stop.

A black poster at the end of the hall recites the story of 1985’s 1000 ‘chameleons’: the year when more than a thousand people were reclassified from one race to another by “the stroke of a Government pen,” based on the color of their skin, the characteristics of their hair, their facial features, and their eating and drinking habits.

Around 702 colored people became white; 19 whites became colored; one Indian became white; three Chinese became white; 50 Indians became colored; 43 colored became Indians; 21 Indians became Malay; 30 Malay became Indian; 249 colored became black; two blacks became ‘other Asians’; one black became Griqua; three colored became Malay; one Chinese became colored; eight Malay became colored and three blacks became Malay.

As I walked further into the museum, I came across a model of the solitary confinement cells, which I could not remain inside for more than a few minutes, given how small and suffocating the room felt, even with its door wide open.

A sign next to the door explains how many black people were imprisoned in such cells, sometimes for up to 540 days, without trial and nothing but a copy of the Bible to keep them company.

The neighbouring room is what I found to be the most chilling and disturbing of all: a ceiling full of nooses of all shapes and sizes, hanging in memory of all those who died in detention but were documented as inmates who committed suicide.

Goosebumps crawled all over me as I looked up at the ceiling, as I , along with everyone else in the room fell into silence – a silence so loud you could hear a pin drop.

The silence is interrupted as I make way into a circular room that houses a projector playing a video of F. W. de Klerk, South Africa’s seventh and last Head of State under apartheid, addressing the black population.

“Don’t push us too far,” he warned while wagging his finger. His statement is juxtaposed with videos showing violence exercised by the regime against black citizens protesting apartheid. “Don’t push us too far,” he said, as if there yet remains a level of cruelty and violence to be reached.

At some point along the tour, I remember the tour guide talking about how the prevalence of violence on both sides of the conflict makes them equally guilty; confidently equating the act of protesting through violent means to a system of institutionalized racial segregation. Trying to establish a grey area within a situation that is clearly black and white.

A few nights later, I attended a screening of Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, a 2013 film chronicling Nelson Mandela’s life, from the days when he was working as a lawyer to the day he became president.

The discussion following the film centered on everyone’s surprise and admiration at Mandela’s ability to forgive those who upheld the system that persecuted him, and the entire black population, for years.

I vividly remember a few of the disapproving looks I got when I explicitly said I would not have been able to follow in Mandela’s steps if I were to experience a quarter of what he went through. “So you wouldn’t have forgiven?”, I was asked, as if one is expected to forgive and forget a system that is designed to solely prosecute them for the crime that is the color of their skin.

Deena Sabry

Managing English Editor

Gallery

The Apartheid museum is a testament to the endurance of South Africa’s racial regime. Although officially dismantled, it remains clear that its memory looms over the nation still. It would be naive to claim that racial discrimination ended with the release of Mandela; huge socioeconomic differences between Blankes and Nie-Blankes persist to this day, demonstrating just how deeply effective the apartheid system was.