By: Omar El Mor

Follow @omarkhaledelmor

The Balfour Declaration may have outlined the makings of a future “national home for the Jewish people”, but at 67 words only it was intentionally left vague and open to interpretation, Visiting Assistant Professor of the Department of history David Speicher told The Caravan.

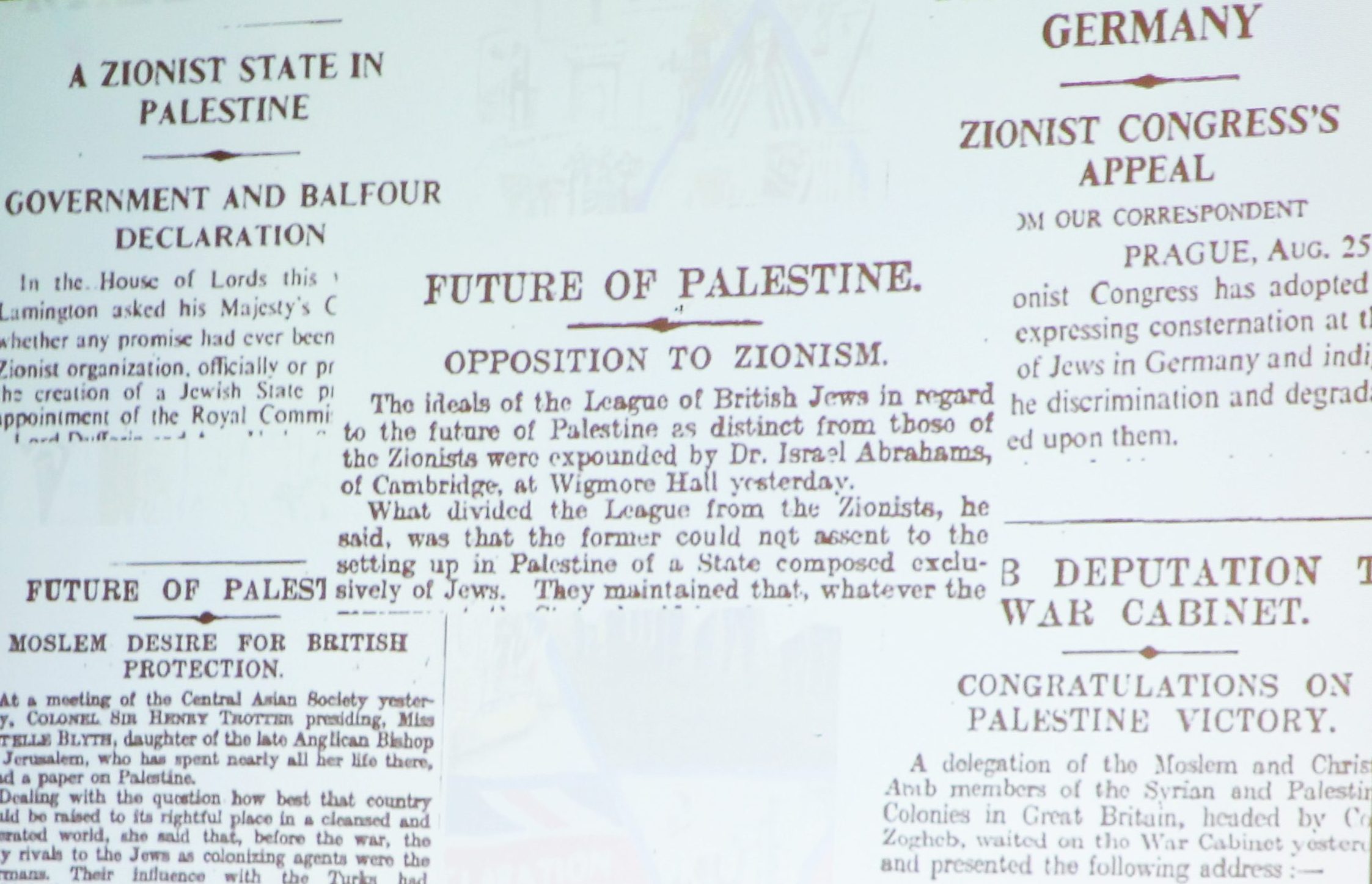

This November 2 marked the 100th anniversary of one of the most controversial publications, that was the backbone of tension in the Middle East — the Balfour Declaration.

The Declaration was written by British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour to Lord Lionel Rothschild, the unofficial leader of the British Jewish community (according to the Rothschild archives on November 2, 1917), just a year before the end of World War I.

Addressing the issue of Jewish migration to Palestine, most historians agree that it was deliberately framed vaguely enough to create flexibility for the British government to negotiate the terms later on.

A century later, they still remain divided over the interpretation and implications of the Declaration.

The Department of History held a conference to discuss these diverging perspectives from the standpoint of the British, the Arabs and the Zionists at the Tim Sullivan Conference Room on the Declaration’s centennial.

“They didn’t state the type of homeland they were talking about,” said Speicher, who tackled the British perspective on the issue.

Speicher added that this style of framing the issue was “consistent with [British] promises throughout World War I”.

Mouannes Hojairi, assistant professor at the Department of History, agrees.

“The British [were] sprinkling promises left and right but those promises are of different scales,” he said.

He also added that Britain made many promises to several nations during the First World War in an attempt to secure its victory by any means.

“France mattered more than any local enemy or ally. That’s why the Balfour Declaration doesn’t touch on the French sphere of influence,” Hojairi said.

Hojairi added that the collapse of France in Europe would impede the momentum of the British. The British were therefore put in a situation where they respected French colonies in the Middle East, but also propagated the Declaration.

From an economic and military perspective, Iraqi oil became increasingly important for the British after they switched their navy from sail to diesel in 1911, Associate Professor of History Michael Reimer said.

In addition, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire on October 31, 1918 made Britain interested in the region for several reasons.

“The British feared Germany’s expansion in the Middle East and the consequences that it will pose if they impeded the trade routes between India and China. The second thing they feared was the rise of the Bolsheviks,” Speicher added.

Running in parallel to that point, it was far more important for the British to maintain their Arab colonies without resorting to armed conflict, which eventually happened anyway after their failure in Iraq.

“The pressures of Nazi Germany in the 1930s would force the British to this specific direction, which at the time was more important than allowing the non-Jewish population the right of self determination,” said Hojairi.

“You definitely don’t want to deal with a demographic majority of a colony if you can deal with a non-native settler minority instead.”

He further said that relying on the non-native settler minority to ensure stability in the region is more convenient for the British as they would be fully reliant on them and that they can trust them more than the natives, whose national aspirations contradicted Britain’s agenda.

One of the most critical questions was addressing the balance of power in the region. “You see this through fact that the “non-Jewish” population in Palestine was not designated as anything but ‘non-Jewish’,” Reimer added.

This omission, amplified to that scale constituted an ‘active omission’, Hojairi said.

Recognizing the peoplehood of a given population would give legitimate grounds for them to invoke nationalist ambitions and the ‘natural’ right to self-determination.

But by calling the native Palestinian population, which were predominantly Arabic-speaking Muslims and Christians, ‘non- Jewish’, that right is overlooked, Hojairi said.

“You’re avoiding calling them anything that gives them a political claim, and so the state could only recognize the political rights of Zionists. It’s an active denial of any political rights for Palestinians.”