Empowering Women About Their Bodies

By: Vereena Bishoy

@vereena_bishoy

While sex education has been a staple of primary and secondary curricula in Sweden since the 1950s, for example, in countries such as Indonesia, China, and Malaysia, proponents of the system have been struggling to raise awareness of its importance in the modern age.

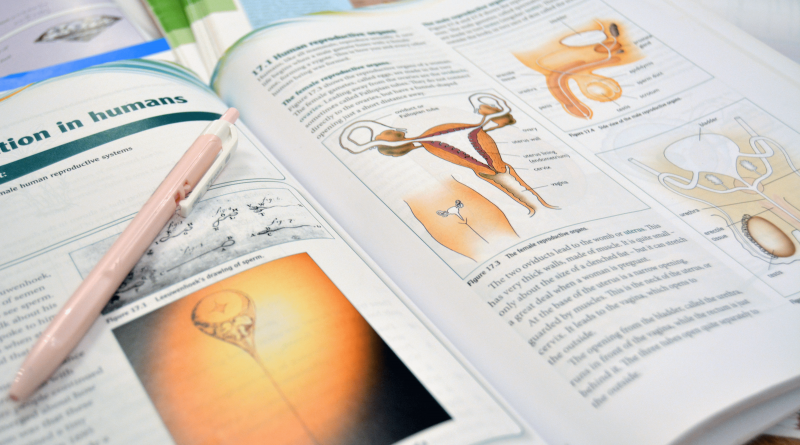

In public schools in Egypt, meanwhile, only a few components of sexual and reproductive health (SHR) themes are addressed, and mostly within the curricula of science classes. According to UNESCO, the SHR parts are frequently skipped by teachers who are unprepared or ashamed to be discussing such content.

In the 1990s, the Egyptian Ministry of Education incorporated a few short lessons on sexuality and reproductive health in the public school curriculum. When the Ministry removed those lessons from the public curriculum in 2010, it said that they would be replaced with in-class discussions. But this has not materialized and many students now lack general knowledge about basic human physiology.

However, support of sex education led by pioneering women on social media platforms in the past few years appears to be gaining ground as content is being created and disseminated to compensate for its absence in the education curricula.

One such platform is The Sex Talk Bel Arabi (in Arabic), an online initiative launched in January 2018 by feminist researcher and activist Fatima Ibrahim, and founding member Eman Soliman.

The initiative provides sex education based on scientific data and prioritizes women’s sexual health issues by bridging their experiences throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

“The idea of creating a group [is] to educate women in Arabic about sexual health and rights with trusted scientific information that is inclusive and positive, and by providing the sex education we never had, making it available for Arab women,” Soliman told The Caravan.

The platform focuses on women’s diverse needs and seeks to end harmful culturally embdedded traditional practices against their bodies.

“Most of the existing terms about sex and gender in Arabic are extremely stigmatizing and give a negative connotation to sexual activities or individuals,” Soliman says.

She believes that this could lead women to hate their bodies. Because current Middle Eastern societies struggle with addressing issues dealing with the female body, gender and sex, these feelings often remain unresolved, exacerbating the stigma even further.

No greater body part is associated with female virginity than the hymen- a thin piece of tissue found near the vaginal opening. Conventional wisdom holds that if the hymen has not been stretched or torn, a woman’s virginity is considered intact.

A torn hymen brings shame to the immediate family or in-laws, particularly for brides. In worst-case scenarios, it may be used to justify honor killings, which some families typically carry out in a bid to protect their sharaf (honor).

However, assumptions about the sanctity of the hymen are problematic at best, because the hymen could tear from vigorous athletic activity – such as bike riding or horseback riding, according to the UK-based National Health Service (NHS).

As a result, some women go so far as to surgically repair or reconstruct the hymen, a procedure called hymenoplasty.

While it is legal in Egypt, it remains out of reach for most, costing up to EGP 23,454.11 ($1270), roughly double the average monthly pay, according to Reuters.

Soliman says that the status of a woman’s hymen can cause “horrific” anxiety among young Arab women from the age of infancy. Popular social norms also hold that a virgin should bleed when her hymen is breached on her wedding night; failure to bleed is considered a sign that a bride was not a virgin before getting married.

But medical science has shown that not all women bleed when they first have intercourse. Some women, the NHS says, may bleed even after having had intercourse several times. More importantly, “having a stretched or torn hymen does not necessarily mean a woman has lost her virginity,” the NHS adds.

In an attempt to combat these social misconceptions and linguistic discrepancies, The Sex Talk Bel Arabi team are currently creating an Arabic dictionary about sexual health terminology. But even in such a pursuit, they’ve run into more difficulties.

“Another obstacle is the public attack from misogynistic individuals who don’t agree with our content, but this one we anticipated before we decided to move our activism to the public space,” Soliman said.

Nevertheless, the group is beginning to receive praise from young women and their mothers who are slowly re-evaluating their self-perceptions and how they discuss issues – which were once considered controversial and shameful because of imposed gender roles.

In one of the comments shared with The Caravan, a user on the The Sex Talk Bel Arabi webpage wrote: “My mom recently followed you, and she now talks to me more openly about sexual issues, and we are able to create that bond because of you.”

Developmental Psychologist and Assistant Professor in the Psychology Department Nour Zaki is one of the few professors at AUC trying to incorporate sex education into their curricula and give it space for ample discussion.

Zaki explained that sex education is thoroughly discussed in the developmental psychology curriculum, a course required of all psychology majors. The topic of sex education appears to resonate the most with her students.

In spring 2021, Zaki invited sex education advocate and doula Nour Emam, creator of the Instagram page, Mother Being to speak about sexual health.

“The sex-ed class was very interesting because she talked about all the things that you barely hear about, like in regular sex classes, like the female orgasm,” said Farida Moharram, a psychology senior, who was enrolled in the class.

Zaki emphasizes that the course doesn’t only address the anatomy of the body and its organs, such as the reproductive system, but also how children adapt to puberty, the concept of privacy, mutual consent, relationships in general, and physical or psychological abuse.

“Sex education is not limited to girls and women; it is a must to all. If sexual education is not taught through trusted sources like parents or in the school curricula, curiosity will lead to acquiring this information through inaccurate and unreliable sources such as online websites and pornographic films,” explains Zaki.

She believes that young Egyptian women often feel humiliation and shame about the changes they experience during puberty and this is due to the lack of awareness, acknowledgment, and acceptance of their bodies’ growth. This ignorance may lead to emotions of shame and humiliation and inaccurate beliefs about themselves and their bodies.

During her discussions with students, Zaki realized the discrepancies in the way sex education was taught in different schools in Egypt.

The root of the problem may lie in how schools pedagogically approach female hygiene and sexual health, or whether they even broach the subject to begin with, she says.

Some schools ask students to study on their own the topic of reproduction found in their biology curricula, but some – including teachers – may find this discomforting so they react with nervousness and embarrassment.

This then creates another obstacle to adequately teaching the topic.

And yet, there are schools that take the time to provide this information through seminars on character building skills. Students say they appreciate the latter approach.