AUC Celebrates Black History Month

By Mariam Ismail

@Mariam_Ismail1

It was February 1976 – 50 years after its inception – when “Negro History Week” evolved into Black History Month.

Only a few years later, the month dedicated to learn more about African-American achievements, history and the struggle towards racial justice, became widespread across the United States.

It is now being observed in Canada and a number of European countries too.

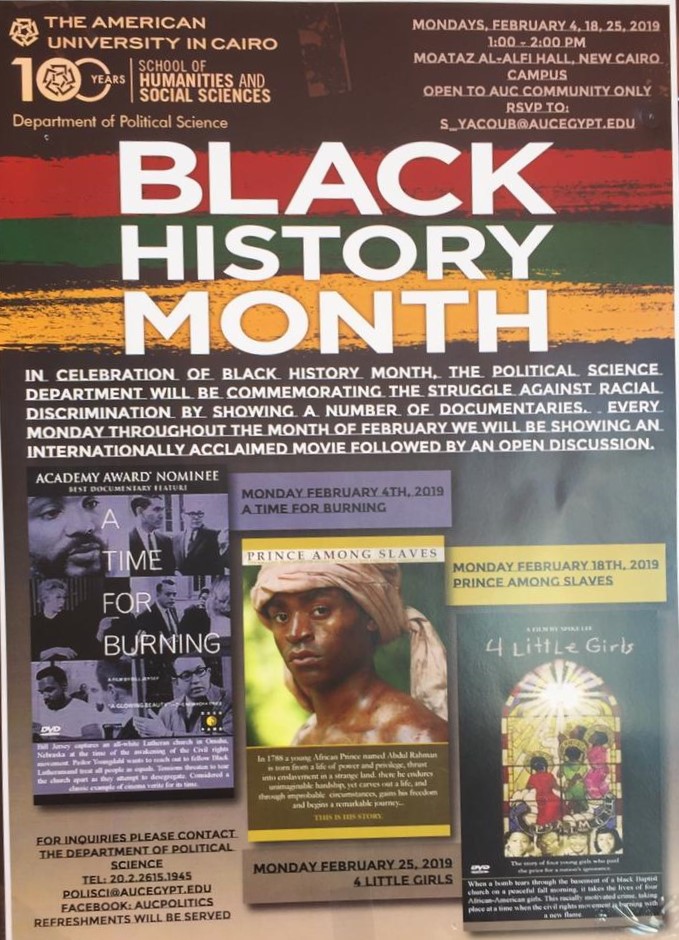

To bring this celebration to AUC, the Political Science Department, led by Rabab El Mahdi, created a series of events to show three documentaries portraying the African-American struggle against discrimination this February.

The events named ‘Black History Month Movies’ were aimed at students in hopes that they would become more informed about racial discrimination and the movements against it.

“Movies might raise awareness more than talks as you get to see the reality of what happened through events and interviews, instead of through the personal perspective of a professor,” Sylvia Yacoub, event coordinator and senior administrative assistant in the political science department, told The Caravan.

The first movie, A Time for Burning, was shown on February 4 in Moataz El Alfi Hall. The 1967 documentary follows Bill Youngdahl, a Lutheran minister in Omaha, Nebraska as he tries to integrate black people into strictly white churches.

According to Political Science Professor Christopher Parker, a black Lutheran philosopher recently told him that this issue is very much still alive today.

“For people who can agree on a set of ideas to be separated across the tracks and meeting in separate places while unable to integrate does show something wrong with the deeper sense of the fabric of American society,” Parker told The Caravan.

While the Lutheran worshipers in the movie all agree on the words of the Bible regardless of their race, the church still proved to be a place where blacks were often unwelcome.

The film sheds light on the institutional and personal racism in Omaha churches where love and acceptance is preached, but not necessarily carried out.

After Youngdahl invites black students to the church for a class and sermon, he is met with the resistance of white people who refuse to enter the church and ministers who believe he is making a mistake.

During one of the meetings where ministers discuss the matter of having a black student present at ‘their’ church, they quote a woman who attends their sermons.

“I want them to have everything I have. I want God to bless them as much as he blesses me, but’, she says, ‘pastor, I just can’t be in the same room with them. It just bothers me.’”

Ernest Chambers, an African-American barber and the main spokesperson for the black community in the film, is constantly arguing with Youngdahl, pushing him to make a difference and lead the change.

He doesn’t applaud Youngdahl for merely showing up, but rather gives him a passionate and eloquent retelling of the black reality which brings to light the injustices of the Church.

One of the most powerful examples is a discussion where Chambers says to Youngdahl, “You are not a house of worshipers, you are a hospital for sinners.”

This is what Parker describes as informal racism, where people are separated by institutions – something which may be relevant to modern Egyptians.

“[Egyptians] have to locate themselves in the world. They have to face these problems in their own country and I think that this comparative politics, or political theory, will help them do that,” Parker says.

He gives the example of AUC, the lush and vibrant campus surrounded by security cameras and high gates, an informal way of separating ourselves.

“How well are we integrated into our community?” he asks.

“We’re doing all this for educational benefits. We’re not selling tickets or trying to gain any profit. Our entire aim is to raise awareness,” said Yacoub.